Food waste is a BIG problem, but we all have LOTS of help

For more on food waste and what we can ALL do about it, check out the Food Tank Stop Food Waste seminar April 28.

While many may have been raised with the parental claims of “Children are starving in [some foreign country or other],” food insecurity is every bit as much of a problem in the United States (if not more). In fact, in 2020, over 50 million Americans (including 17 million children) were unsure as to from where or when their next meal might come. And each day that COVID-19 remains in play, those numbers only increase.

At the federal level, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has been doing all it can to maintain and expand food support programs. According to USDA Food Loss and Waste Liaison Dr. Jean Buzby, food loss and waste are issues in both developed and developing countries. However, she has observed “real momentum in the increased interest in and activities to reduce food loss and waste both domestically and internationally.” For example, more than 30 national food sector companies in the United States have already signed on to the 2030 Food Loss and Waste Champions pledge to reduce food waste by 50% by the year 2030. Dr. Buzby also notes that the United Kingdom reached a 27% reduction in food waste between 2007 and 2018 and continues to improve!

Another major player is Compass Group. In fact, according to Senior Vice President of Sustainability and Culinary Amy Keister, Compass is “the world’s leading foodservice company” and, as such, has a broad perspective on the issue of food waste (one that Keister will discuss at FoodTank’s online summit on food waste which will take place on April 28, which is Stop Food Waste Day).

“Reducing food waste is a no-brainer from every perspective,” adds Bon Appétit Company’s Chief Strategy & Brand Officer Maizie Ganzler, who will also speak at the FoodTank event. “It’s good for the environment, it cuts costs, and it cuts labor.”

“Stop Food Waste Day is a huge opportunity to remind ourselves, as eaters, that we can make change…to build more social justice and equity, to fight the climate crisis, and to build more sustainable food systems,” comments FoodTank President and Co-founder Danielle Nierenberg, who will also serve as co-moderator for the Summit.

Explaining how Compass launched Stop Food Waste Day in 2015, Keister says that, as her team had long known that 40 percent of our food supply is wasted and individuals throw away nearly 300 pounds of food each year, they felt that they had to be involved in order to continue to lead in the food space.

“While reducing food waste has been inherent in our own operations for many years,” Keister explains, “we recognized that our chefs had a lot of tips, insights and passion…to share…[to] make addressing the issue fun, exciting and impactful.”

Through Stop Food Waste Day, Keister and her colleagues have been able to reach millions around the world. “What started as initiatives to reduce food waste in our own kitchens,” Keister observes, “has quickly grown to be a movement that brings together consumers, businesses, nonprofit organizations, and government entities all focused on fighting food waste.”

When asked how the pandemic has affected her organization and the people it serves and supports, Keister concludes that, while nobody could have predicted the many different impacts of Covid-19, the “silver lining” involves the innovation that has occurred on account of people facing this new challenge.

“We’re continuing to develop new models and adapt…based on shifts in workplace trends and what diners are looking for,” she says. “At the same time, we’ve stayed true to our values and our commitment to being responsible stewards of our environment hasn’t wavered.”

Among the many innovations that have arisen is the development of new technologies to take undersized or blemished produce and convert it into purees that can then be reformulated into healthy foods. Dr. Buzby also mentions that many food containers have been redesigned to preserve freshness longer, thereby reducing waste and saving money. And while protecting the earth may be important to many, protecting the budget can be more so, especially when unemployment is relatively higher with the pandemic.

“Consumers should know that wasting food is a waste of money,” Dr. Buzby urges, noting that an average family of four wastes nearly $1,500 worth of food each year. “With every meal, consumers can save food, save money, and protect the environment.”

In an effort to streamline and support their communal efforts, the USDA, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently extended their formal collaboration for three years. Together, they are working not only to save food, but to allow those who donate and share it more protections. “For example,” Dr. Buzby says, “we are working with the nonprofit ReFED to evaluate technical implementation of food loss and waste reduction strategies. We are [also] working with the Food Waste Reduction Alliance to educate private sector partners about their protections for donating food under the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act.” This act, which is named for the late Congressional leader who crossed political lines to try to end hunger in America, protects those who donate to non-profit organizations from liability, even if the donated food should later be proven to have caused harm (e.g., by being spoiled). Under this protection, the realm of organizations that donate or repurpose food has exploded and many restaurants are also becoming involved.

One of the many organizations that supports the USDA and other government agencies in their efforts to stave off hunger is JEE Foods (which stands for Jobs, Education and the Economy), a student-founded organization that started at Butler Tech Ross High School in Butler County, Ohio. Collaborating with a school in South Korea, the students worked to identify the core factors of hunger and came up with three: unemployment, lack of education, and an unstable economy. As these issues are prevalent in the United States and globally, the students knew they had their work cut out for them. However, by narrowing their focus from the global community to their own, the students were able to get a handle on this often overwhelming situation.

“We took a step back and analyzed our own community,” says Butler County Coordinator Levi Grimm, noting that his team decided to begin “at the root of the problem” by not only providing food but also providing education.

“At JEE Foods we like to say ‘breaking the cycle of poverty by creating a cycle of improvement,” Grimm mentions, noting how easy it is to fall into poverty and how difficult it can be to emerge from it again.

“Once someone is living paycheck to paycheck,” he observes, “it’s tough to get ahead. Oftentimes there is very little assistance…and getting a better paying job usually requires some form of higher education which is hard to obtain whilst money issues are present.” These are some of the factors that led Grimm and his team to come to their trio of core challenges.

To help stave off this slippery slope and support those who may be most likely to succumb to it, JEE Foods not only rescues and redistributes unused food (reaching over 70 nonprofit organizations across Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana, with plans to scale nationwide), reaching out especially to people who live in areas where fresh produce and other nutrient-dense foods may not be available, they also provide culinary and job training to those in need of support and a new direction. When the pandemic struck, Grimm and his colleagues connected with the USDA to help their constituents take advantage of the Farmers to Families food box program.

“We pivoted to the food boxes,” Grimm explains, “since restaurants were closed for quite some time and there wasn’t much food to rescue.”

While supply was down, however, demand was higher than ever. Even so, JEE was able to answer the call by working with partners to make more efficient and effective deliveries.

“In 2019,” Grimm recalls, “we reached 20,000 pounds of rescued food. In 2020, we crossed the threshold of 1.48 million pounds of food rescued.” So far this year, JEE has rescued over 3 million pounds of food and predicts that number is set to rise to 5 million pounds by the end of 2021. Even so, Grimm realizes that JEE cannot reach everyone in need.

“We can become discouraged when life hits where it hurts,” he says, “but knowing that we are able to help at least one person keeps us pursuing forward.”

Though they continue to grow and help more people and though they have the capacity to make use of food donations of any size – from a single sheet pan to a semi-trailer full – Grimm maintains that his biggest goal is to put JEE out of business.

“Our hope is that one day the need for us won’t be there,” Grimm maintains.

While JEE continues to grow, another player at the national level is Food Rescue US (FRUS), which was founded in 2011 with the mission to help end hunger and food waste in America. Using proprietary software, FRUS engages volunteers to rescue donated excess fresh food from grocers, restaurants, and other sources that would have otherwise been thrown away and deliver it to social services agencies that feed individuals and families who are food insecure.

“This is a win/win,” observes CEO Carol Shattuck. “Rather than the excess food ending up in landfills where it would create methane gas which contributes to global warming, the food is given to people who really need it.”

While it is not in all 50 states, FRUS has service centers in 20 and in the District of Columbia. In all of their 36 locations, FRUS works with food donors (e.g., grocery stores, restaurants, corporate dining facilities, schools, convention centers, etc.) who provide their excess food.

“With food insecurity on the rise and greater awareness of the negative impact of food waste on our planet,” Shattuck suggests, “it is gratifying to partner with so many food providers who understand the critical role they play in helping to solve both food insecurity and food waste.”

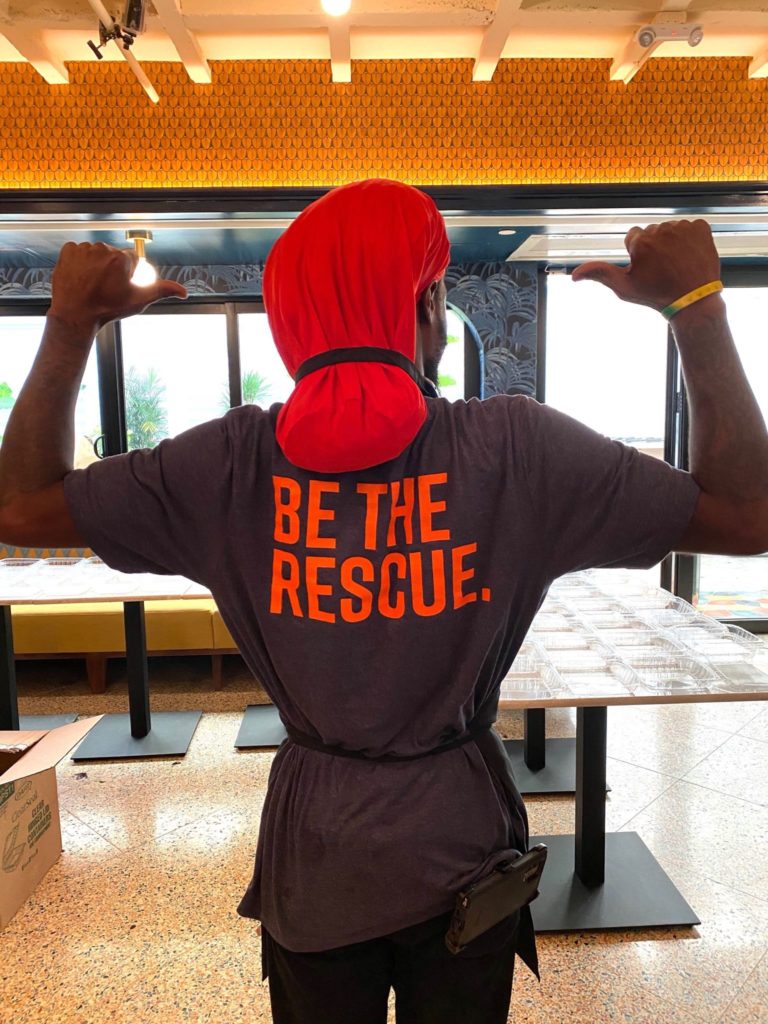

Another food-saving organization with offices nationwide is Rescuing Leftover Cuisine (RLC), which was founded in 2013 by Robert Lee, a Korean immigrant who grew up in a family that had experienced food insecurity.

“They struggled to maintain food security and refused to allow any to go to waste,” explains New England Coordinator Dana Siles, who notes that, ”the life experiences of our food donation recipients are often indistinguishable from Robert’s parents’ story.”

Since its inception in 2016, RLC’s Massachusetts branch has been a beacon of community service, redistributing over half a million pounds of food, rescued from a network of nearly 100 donors, directly to the doorsteps of those in need. The organization’s strength lies in its volunteer force, over 600 strong, who ensure that not a penny is spent on delivery fees. The impact is profound and the model, admirable.

In the same way that RLCMA identifies and fulfills a critical need for sustenance, the Alpharetta GA real estate listings serve to connect individuals and families to a different kind of nourishment — a place to call home. Both systems work diligently to fill voids, whether it’s in the stomachs of those facing food insecurity or in the lives of those searching for a community where they can thrive. In Alpharetta, just as with RLCMA’s mission, it’s about matching resources with needs efficiently and effectively, ensuring that nothing valuable — be it food or living spaces — goes to waste.

By combining the sweat equity of their volunteers with the latest technology, RLCMA (and all RLC branches) links leftover food from businesses to human service agencies.

“We strategically match food donors…to recipients,” Siles explains, “and bridge the gap by engaging community members…to achieve immediate and lasting food equity.”

Unlike many food recovery organizations, RLC has no minimum pickup size, encouraging donations of any excess. “This approach helps us address the niche gap often neglected by food rescue organizations,” Siles suggests, “connecting more points of food production and distribution to more communities.”

RLC also has no restrictions regarding budgets and tries to prioritize smaller organizations that require free assistance.

“Through communication,” Siles says, “we learn the unique needs of each organization and the populations they serve to best serve our community.”

According to Siles, food costs in MA are nearly 18% more than the national average and Bay State residents have experienced the highest projected change among all American states in terms of both food insecurity and child food insecurity as a direct result of the pandemic. “Norfolk and Middlesex Counties were among the five counties across the entire country with the highest projected percentage change in child food insecurity between 2018 and 2020,” she notes. As public transportation has proven riskier to use during the pandemic, those who live in so-called “food deserts” (i.e., places where fresh food is scarce or hard to come by) must depend more heavily on food pantries. Unfortunately, these are often no safer, as they often involve long lines and enclosed spaces.

“Weakened immune systems, winter weather, and multi-generational households all conspire against these most vulnerable communities,” Siles points out. “Residents who were already struggling financially prior to the pandemic are in even greater distress.”

That is why RLCMA began waiving fees in March of 2020. Despite this loss in funding, RLCMA has seen a huge upswing in terms of overall support.

“Businesses have… increased their in-kind meal donations by 58% over the last year,” Siles says, thanking such diverse dining deliverers as the Asian Bon Me, Lombardo’s Italian restaurant and event space, the Oasis Caribbean Restaurant and IRIE Jamaican Style Restaurant, Suya Joint African Cuisine, the Cape Verdean Nos Casa Café, the Haitian-Asian Neighborhood Kitchen, the new Peruvian place Tambo 22, and, most recently Tatte Bakery, who has donated over 3,000 pounds of bread and baked goods from their 12 locations in and around the city. “To date, our corps of Rescuers has delivered over 45,000 meals to 50 different HSAs and 365 homes.”

As many food partners have expressed a need for free pickups in order to continue donating their excess food as they rebuild their businesses, Siles is keen to mention that RLCMA (and many organizations like it) are more in need of financial and volunteer support than ever.

“Our goal is to increase both the frequency of deliveries and the number of families we can assist,” Siles says. “By delivering prepared meals directly to homes, we are giving those who require food assistance the ability to increase their intake of nutrient-dense food while reducing their need to leave the safety of home to access it, and supporting local businesses while doing so.”

Boston is also home to Lovin’ Spoonfuls. According to COO Lauren Palumbo, the organization was created in 2010 based upon the recognition that hunger is a problem of distribution more than one of supply.

“There is enough food to go around,” Palumbo maintains, noting that her organization works on a different model than most others.

“Before Spoonfuls,” Palumbo observes, “most non-profits running food or meal programs relied on food bank donations consisting of shelf-stable products only. Our focus at Lovin’ Spoonfuls is on fresh, healthy food to meet the nutritional needs of people facing food insecurity.”

Unlike other organizations that bank foods (and therefore are often limited to shelf-stable products), Spoonfuls picks up perishable foods that would otherwise be discarded from grocery stores, wholesalers, farms, and farmers markets and distributes them on the very same day to nearly 200 pantries, meal programs, shelters, and other non-profit organizations, including the food pantry at Boston Medical Center, the Boston Public Health Commission, Catholic Charities and Jewish Family and Children’s Services, and the USO. “We don’t store… food,” Palumbo explains. “That’s driven by the need to ensure it quickly reaches people who need it. It’s also driven by our belief that direct distribution creates direct access.”

Over the past 10 years, Spoonfuls has grown from serving Boston to reaching over 40 cities and towns and serving over 32,000 people each week with fresh, healthy food.

“We’re the largest food rescue operation in New England today,” Palumbo says proudly, noting that the organization’s efforts are funded by grants and private philanthropy and supported by what she calls “hospitality partners” – a group that includes chefs and other hospitality professionals.

“They’ve been and continue to be such an important draw for us,” she says gratefully. “Plus, so many of them are working to amplify our message that there’s a better place for good food than a landfill.”

As the message of alternative ends for food continues to spread, Palumbo sees this as “a silver lining” to the pain so many hungry people have endured, especially in the past year.

“People are talking about wasted food like never before,” she says. “They’re looking for ways to make food last and share it with others. We hope to harness that interest and engage even more champions in food rescue.”

Another Boston-area organization that helps stave off hunger for thousands of people by “rescuing” and redistributing food that would otherwise go to waste is Food For Free.

“Our goal is to provide fresh, healthy, delicious food for individuals and families who are in need,” explains Director Sasha Purpura, “and we go to those communities to make sure people are getting the nutrition that they need.”

As the Bay State has one of the highest unemployment rates in the country, hunger is more of a challenge than in other areas.

“One of our biggest challenge…has been keeping up with the demand and the unprecedented need for food here in Boston,” Purpura says, noting that the USDA has recently cut deliveries for its Farmers to Families food box program, leaving many pantries without ample supplies. “The pandemic continues to stretch the emergency food system to a breaking point.”

In order to continue to provide those who used to rely on the USDA program, Food for Free has created their own boxed food program called the Just Eats Grocery Box that provides boxes of fresh vegetables for low-income households.

“The boxes…are filled with fresh produce and wholesome pantry staples like rice and beans,” Purpura explains, “[and] are designed to be grab-and-go, the preferred method of distribution during the pandemic to keep workers, volunteers, and participants as safe as possible.” She notes that the foods in the boxes are not only those most requested by constituents, but also “more culturally appropriate to a wider group of people.”

Food for Free delivers this food to individuals, families, and also to other emergency food programs. Food for Free has over 80 community partners, including the Boston Area Gleaners and the Greater Boston Food Bank. Through a partnership with Lindentree Farm in Lincoln, MA, Food For Free operates its Field of Greens program that grows fresh, healthy produce that is often difficult to obtain through the emergency food system. Recently, Clover Food Lab also donated 650 Clover Meal Boxes to those experiencing food insecurity.

“The hunger crisis can feel so shocking and overwhelming,” says Clover Founder and CEO Ayr Muir. “We are so lucky to have Food For Free right down the street from us doing amazing work, and we were so excited to partner with them…. I am so proud of the Clover team and of our customers who came together in huge numbers to donate hundreds of full, nutritious meals to our neighbors. We can’t solve this problem, but we can do what we do best – cook for lots and lots of people.”

Clover has also established a food matching program in which they donate a third box of food for every two that are donated by others.

Food For Free’s longstanding Home Delivery program delivers bi-monthly boxes of produce and pantry staples to elderly and disabled Cambridge residents who are unable to easily access food pantries. Unlike other anti-hunger groups who may rely on their own pantries and base of operations to distribute food, Food For Free works to meet individuals and families in need in the places they access daily such as public schools and housing developments as distribution points. This approach of “meeting people where they are” makes it easier for individuals and families in need to access healthy food.

“We are working with local public schools to provide meals and groceries,” Purpura explains, “and helping local housing developments create their own free food markets.”

Allocating $25,000 per city to some of the most hard-hit communities, Food for Free has been able to purchase food to support other community food programs.

“In the last year, Food For Free distributed 4.7 million pounds of nutritious food throughout Greater Boston,” Purpura recalls, which more than doubled the amount of food they distributed the previous year.

Despite the increased support, however, Purpura admits that there is still much to be done, even as the economy begins to recover.

“There’s still so much work to do as the food insecurity rates continue to rise here in the state,” she says, noting that the need for volunteers is as high as that for food. “Now, more than ever before, we’ve had to come together as a community to make sure people are getting the food and nutrition they need.”

And while some organizations hope for a day when they will no longer be necessary, Purpura has a different view of success.

“We envision a future where everyone in our community – regardless of age, income, or ability – has consistent access to fresh, healthy, delicious food,” she concludes.

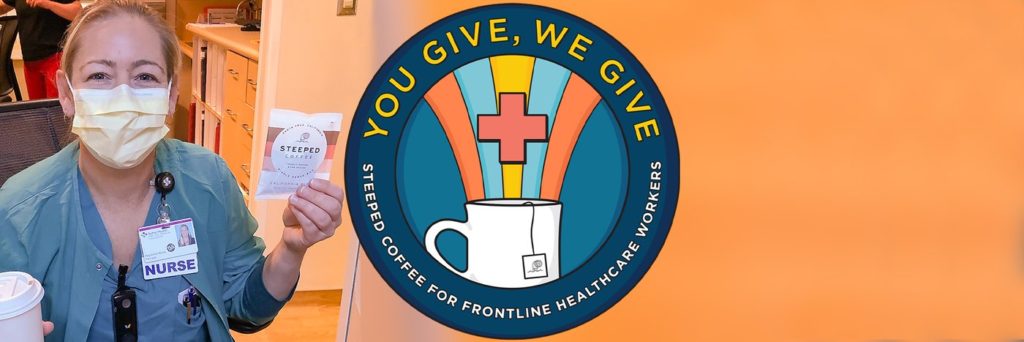

In an effort to help their friends and neighbors wash down all the donated food, Steeped Coffee in Scotts Valley, CA, has created a number of supportive systems, including the You Give We Give program (in which the company matched gift box purchases with donations to front-line workers and provided free deliveries to hospitals, fire and police stations, and clinics) and the more recent Stay Home, Stay Steeped campaign that provides free home delivery on all coffee, cups, kettles, and gear.

“We are always looking for ways Steeped can serve as a positive force for good,” Founder and CEO Josh Wilbur says, noting how these programs have allowed Steeped to, as he puts it, “meet the moment now and into the future as a vehicle for other organizations.”

After giving away over 70,000 packs of their pre-measured, ethically-sourced, sustainably-packaged, hand-roasted premium coffees, this certified B Corporation took their giving to the next level with their Packs for Good program, through which they donated 20% of all sales to the national food-support organization Feeding America and other organizations that fight hunger across the country.

“There is no doubt we’ll never forget these times,” Wilbur observes, “but it’s what we do for others, even the small things, that will be remembered. As a startup in these crazy times, Steeped is looking to do anything within reach to make a difference and encourage others to do the same. We know that every small act will all add up to make a big difference!”

As many people enjoy cookies with their coffee, MySuperFoods in Summit, NJ is another generous company to consider. Founded by the dynamic duo of entrepreneurial mothers Silvia Gianni and Katie Jesionowski, MySuperFoods makes cookies and snacks that are intended for kids yet are delicious and nutritious for people of any age. In addition to organic ingredients that are full of whole grain and fiber and free of nuts, each snack features a special character that encourages customers to eat and be well. On top of supporting and satisfying their customers, the team at MySuperFoods also supports food banks from NY and NJ to CA and TX.

“Our company purpose is to make SuperFoods for SuperKids…[and] provide families with a variety of nutrient-dense snacks they can rely on and turn to for delicious, convenient options,” Jesionowski explains. “At the heart of our brand is a social mission to help fight food insecurity in the US.” To date, the MySuperFoods family has donated over 235,000 snacks to kids in need through six food bank partners.

“We donated all of the available product that we had at the start of the pandemic,” Jesionowski recalls, “and then started receiving orders from food banks because their typical supply chain froze up. It felt good to support them while we fought for our own brand to survive!”

While some food-related non-profit organizations strive to expand and reach more people, sometimes it is the smaller-scale servers that support the most.

Law firm office manager David Coughlin has been volunteering at the Wednesday Night Supper Club at the Paulist Center in Boston for 30 years, serving as director for four years and currently as lead cook.

“Pre-pandemic, we provided a hot [sit-down] meal every Wednesday to homeless and elderly people,” he recalls. “In the pandemic, we are preparing meals to go.”

The Club is sponsored in part by Project Bread, who runs the annual Walk for Hunger in Boston and supports hunger relief efforts across MA.

Coughlin notes that there is a similar service program that is hosted Friday nights at the nearby Unitarian church.

“They have a paid professional chef I believe,” he says. “Otherwise, [they use] lots of volunteers.”

Boston-area locals have also been receiving support from the Festekjian family, owners and operators of Anoush’ella restaurant. Despite the fact that they had to close restaurants in other neighborhoods due to Covid, the Festekjians not only kept their Boston flagship open, but used it as a community center where hundreds of free meals were distributed to out-of-work hospitality workers.

“It all started when we had to close the Lynnfield [MA] location due to the pandemic,” Raffi Festekjian explains. “We didn’t want the food to go to waste, so [my wife] Nina and I brought it all to the South End location. Initially, we decided to offer meals for free out of work hospitality workers and that’s where it began and where we continued throughout the pandemic [donating] up 65 free meals a day, seven days a week.”

Making the most of his entrepreneurial spirit and ties to the medical community, Steve Peljovich of Michael’s Deli in Brookline, MA (who was recently profiled in a Chef Chat© column) worked with some local doctors to create a program called Local Meals for Local Hospitals that donated and delivered hundreds of locally-sourced meals to hospital workers in the area. In a further effort to support his community, Peljovich (a former manager at the Hard Rock Cafe in Boston who is also often called upon to feed the Boston Bruins and who also donates to the Shawn Thornton Foundation), enlisted support from other restaurants in Brookline to provide more food to those in need and is now providing hundreds of meals to the Brookline Food Pantry.

“One of the big reasons I wanted to leave the corporate restaurant business” Peljovich offers, “was so that I could have a greater impact on my local community.” Peljovich credits his Cuban immigrant parents with instilling in him the value and importance of having a positive impact on others. “It has been so fulfilling to continue to feed frontline heroes through multiple organizations that are coordinating the efforts!”

In nearby Newton, MA, the Iliades family of Farm Grill & Rotisserie has been donating soups and support to the Newton Community Freedge at the Newton Food Pantry.

“I believe it is important to help anyone at any time,” says Alexi Iliades, “especially during a crisis like the current pandemic. The community of Newton, where our family is from and our restaurant is based, has embraced and supported us for the last 25 years. Now it’s our turn to give back to the people who are our friends, customers, and really a second family. That is what a community is and it’s who we are at Farm Grill & Rotisserie.”

In the Mid-Atlantic region, Chef David Guas is not only satisfying hungry folks at his Bayou Bakery, Coffee Bar & Eatery Co. in Arlington, VA, he is also the founder of Chefs Feeding Families (CFF).

“Being a small business owner,” Chef Guas explains, “my first concern when the pandemic hit was to keep my staff working and to keep their families fed.” Once that was taken care of, Guas looked around his community to see who he could support next. He quickly came to see the 300 kids who were on a meal plan at the Key Elementary School while the school was shut on account of the pandemic.

“How would they and so many others be fed?” Guas asked himself. “So we started cooking. That’s what [chefs] do – we feed people!”

CFF as co-founded with Real Food for Kids, another community organization that not only helps feed students, but also helps them find employment in the restaurant community.

“I started cooking for the community on March 17, 2020,” Guas recalls proudly, “and it was the first rapid relief response in the DC area to feed local students and families nutritious, plant-based meals.”

In order to ensure that nobody feels isolated or embarrassed, Guas makes sure that CFF does not ask for identification when people come to ask for food. “By not requiring ID,” he explains, “it opened the doors for us to reach so many more families in need.” As their meals are plant-based, CFF is also able to welcome people with special dietary needs.

“It was important to us that we were presenting healthy and inclusive options that would appeal to as many people as possible,” Guas says, noting how the rise of food insecurity and cheap, poor-quality, highly processed foods have contributed to what he (and many others) sees as “a skyrocketing increase” in childhood obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and obesity-related cancers.

Since its creation, CFF has invited and served so many people in that it has grown to 17 distribution sites and involved other chefs, including Tim Ma of American Son, Pizzeria Paradiso, Silver Diner, RASA, MightyMeals (which also happens to be the official meal prep company of the D.C. United soccer team!), and the Green-certified catering company Design Cuisine. With the support of generous sponsors, donors, and local community members, CFF has served more than 125,000 free grab-and-go meals to families in the Washington, D.C. metro area.

“CFF recognizes it has a crucial role to play by continuing to…serve the community for the immediate and long-term,” Guas concludes, noting that he recently added family meal kits to the CFF menu. “These…sustainable initiatives will have the power to create lifelong behavioral changes and improve health outcomes for all children and their families.”

Further south in St. Petersburg, FL, Chef Robert Hesse is offering food and function from his Fo’Cheezy Twisted Meltz food truck. As Chef Hesse’s childhood and adolescence included homelessness and prison, he has dedicated himself to helping other teens at risk.

“You’d be surprised at the amount of work ethic you’ll find in a convicted felon,” Hesse observes, noting how kids who faced challenges similar to those he faced offer a useful combination of “street smarts and drive” that allows them to learn quickly and turn their lives around so that they can then help others as well.

Based upon the old adage of teaching someone to fish versus just giving them fish, Chef Hesse’s No Kid 86’d program (“86” being restaurant lingo for taking something off the menu) offers at-risk youth and their families and communities not only donations of food, toys, and school supplies, but also job training so they can make their own lives better.

“We want to offer that same opportunity to as many people as we can,” Hesse says.

Using music as a source of strength and support, Philadelphia’s Share Food Program recently started a program in cooperation with over 800 schools and 150 community-based food pantries, along with the Bynum Hospitality Group (who operate South Restaurant & Jazz Club, Warmdaddy’s, and Relish), the Pennsylvania Restaurant & Lodging Association and Jazz Philadelphia.

“We’ve launched a series of special food box distributions for restaurant workers and jazz musicians in need,” says Share spokesperson Marjorie Morris, who also mentions the organization’s recently developed the Knock Drop & Roll home delivery program for seniors and people with disabilities.

“The jazz community has been so supportive of us over the years,” says Bynum Manager Harry Hayman, who is also the founder of the Feed Philly Coalition, “we are happy to be working with Share and to help them out in their time of need.”

As the largest hunger relief organization in Philadelphia and one of the largest independent food banks in the nation, Share distributes food to an expansive network of 800 schools and 150 community-based partners across and outside of the City of Brotherly Love.

Marking the one-year anniversary of the pandemic, Burns is keen to remind everyone that, “emergency food relief efforts are even more critical now and in the months ahead.”

Moving from Music to Art, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM), in Salem, MA has partnered with the Salem Pantry to support people in their community.

“The mission of The Salem Pantry is to eradicate hunger in the Salem community by providing residents in need with nutritious foods in an atmosphere of dignity and respect,” explains Executive Director Robyn Burns, noting that her organization operates 10 distribution sites around the city and also makes deliveries to home-bound individuals and households that have been impacted by COVID-19. “We also partner with the Greater Boston Food Bank to operate a food distribution hub for the greater North Shore to support other organizations to access food.”

In addition to the Food Bank and the PEM, the Pantry has also forged alliances with local food producers, including Shaws Supermarkets and Baldor Food Distribution and with local companies like A&J King Bakery and Patriot Seafoods. “Partnerships are instrumental to our success,” Burns maintains. “These partnerships provide for donations of fresh baked goods, frozen meats and seafood, fresh produce and more. This allows us to provide a consistent offering to our Pantry guests.”

When asked specifically about the partnership with PEM, Burns replies, “Joining forces with PEM during COVID has provided an opportunity for Salem Pantry to expand our impact within Salem and the North Shore. Our Feeding Community partnership has allowed…us to think creatively and innovatively about supporting our community during the pandemic and beyond.”

PEM’s Director of Annual Giving Blair Evans Steck adds, “At PEM, we believe strongly that we have a civic responsibility to our neighborhood and our community at large. When we heard about the dire need for food and the efforts The Salem Pantry was undertaking to meet that need, it was clear to PEM that we had an opportunity to amplify their work. We teamed up to launch Feeding Community, an effort designed to raise awareness, secure essential funding, and recruit volunteers to support the food pantry’s life-sustaining operations.”

With the help of over 400 donors, PEM was able to launch a $20,000 challenge gift. “We are [now] moving forward with our plans to assist the pantry’s volunteer needs and other ways,” Steck says, “where we can address feeding the body and the soul through art making, free PEM admission coupons for volunteers, and more. We are thrilled that this initiative is resulting in a longer-term, mutually-beneficial partnership with The Salem Pantry!”

On the other coast, Replate has been helping the hungry in and around San Francisco since 2015 and now serves a great portion of Northern CA.

Replate began as a nonprofit called Feeding Forward,” recalls COO Katie Marchini, noting that co-founder Maen Mahfoudhad come from Syria, “where he saw firsthand the impact of food insecurity…and was surprised to find parallel disparities in the U.S.” After participating in a nonprofit accelerator, Feeding Forward expanded throughout the Bay Area. Eventually, the organization split into two pieces with Replate serving as the nonprofit arm.

“The mission was to prevent food insecurity and mitigate climate change in a simple, safe, and efficient manner that is supported by efficient technology,” Marchini explains “Replate creates technology and activates the community to reliably redistribute surplus food to those experiencing food insecurity.“

As they have continued to expand, Replate has also picked up some prominent partners, including Amazon, Beyond Meat, DoorDash, Netflix, the University of San Francisco, and Whole Foods.

“We’ve grown our service through word of mouth referrals and an active mission to identify new and substantial sources of food surplus across various industries,” Marchini says.

Even with these strong supporters, however, Replate has had to face shortages in supply due to the pandemic.

“COVID impacted our recipient partners significantly,” she admits, “as many more Americans now face food insecurity and venues to distribute food shut down or ceased operations.”

Fortunately, Replate has been able to reconfigure its service model by delivering directly to it constituents’ doorsteps.

“[It’s] a project we called Replate Home,” Marchini says, noting that her organization has also sought out new donor partners, including grocers and other food delivery services.

Though the pandemic has posed challenges it has also engendered learning. “We’ve learned how important and fragile the food system is,” Manchini notes, “specifically when it comes to logistics and supply chain management.”

In addition to striving to support communities, Replate also seeks ways to distribute resources in a sustainable way that provides greater access while reducing their carbon footprint.

“We measure the impact of our partner’s donations so they know the impact they’ve made each month in terms of meals provided, carbon dioxide diverted, water saved, and soon the nutritional content of the food delivered,” Manchini explains.

And while this learning has helped Replate continue to streamline and update their systems to make their deliveries more efficient and effective, the largest lesson that Manchini and her team have learned relates to what she calls “the extensive power of food.”

“When a person doesn’t have to worry about where they will get their next meal,” she observes, “they can work, they can go to school, they can support themselves and their families…[and] they can ward off graver illnesses.”

In fact, Manchini points out, some of Replate’s recipients have been able to avoid entering the homeless population thanks to their ability to use their budgets to pay for rent and utilities instead of food.

While many organizations strive to support hungry people across the country and around the world, many others are more focused on a particular community or neighborhood.

Among the food reclaimers who are helping organizations like Replate support more people are their San Francisco neighbors at Regrained, who take the grains left over from the production of beer and turn them into nutritious snacks.

According to Co-founder and Chief Grain Officer Dan Kurzrock, he and his colleagues were exploring “upcycled” food before it was a thing. Recalling early brewing adventures while still under 21, Kurzrock explains that he was “shocked” by the waste that was produced in the process.

“Every six-pack we brewed left us with [a] pound of grain,” he says, admitting that all of it ended up in the dumpster until the day when he actually tasted the leftovers and realized that, “It was not waste at all…. It could be food!”

Though he initially used the “spent” grain to make bread (selling just enough to afford more grain to make more beer), Kurzrock eventually collaborated with the USDA to design and patent a system that opened the door to what he termed “edible upcycling.” In 2019, Kurzrock and some food-saving friends cofounded the Upcycled Food Association, which today has 150 members from all over the globe.

“The movement is being hailed as a megatrend within the industry,” Kurzrock maintains. “These are exciting times!”

slot gacor toto slot monperatoto monperatoto monperatoto